Published in 2018, The Salt Path told the story of Raynor Winn’s 630 mile trek along the South West Coast Path with her husband Moth. They walked in the shadow of homelessness, a devastating medical diagnosis and financial ruin. The couple’s story inspired hope and resilience as countless people hit the trail to follow in their footsteps.

The Salt Path, which has sold over 2 million copies, was billed by the publishers as “unflinchingly honest”. But it seems that may not be the case. Last Sunday, the Observer printed an in-depth investigation into the book, with serious allegations about the author’s financial embezzlement and misrepresentation of the couple’s homelessness, as well as doubts over Moth’s health condition.

The author initially called the report “highly misleading” and published a lengthy rebuttal alongside taking legal advice. The publisher, Penguin, issued a statement in defence of its due diligence. Meanwhile, PSPA, a health charity associated with the couple, cut ties with them and reassured its supporters. Further distribution of the recent film adaptation, starring Gillian Anderson and Jeremy Isaacs, may be in doubt. Social media has been characteristically vitriolic and polarised in its response.

In short, it’s a mess.

With so many claims and counterclaims, it’s simply too soon to tell exactly what went wrong. But it’s clear that nonfiction demands that writers tell the truth and that readers are able to believe them. The Salt Path seems to have failed that basic test.

The fragility of memory

Since I started writing about walking, wonder and wellbeing, I’ve often been asked about The Salt Path. Someone even bought me a copy, though I’ll admit it’s still on my bookshelf waiting to be read.

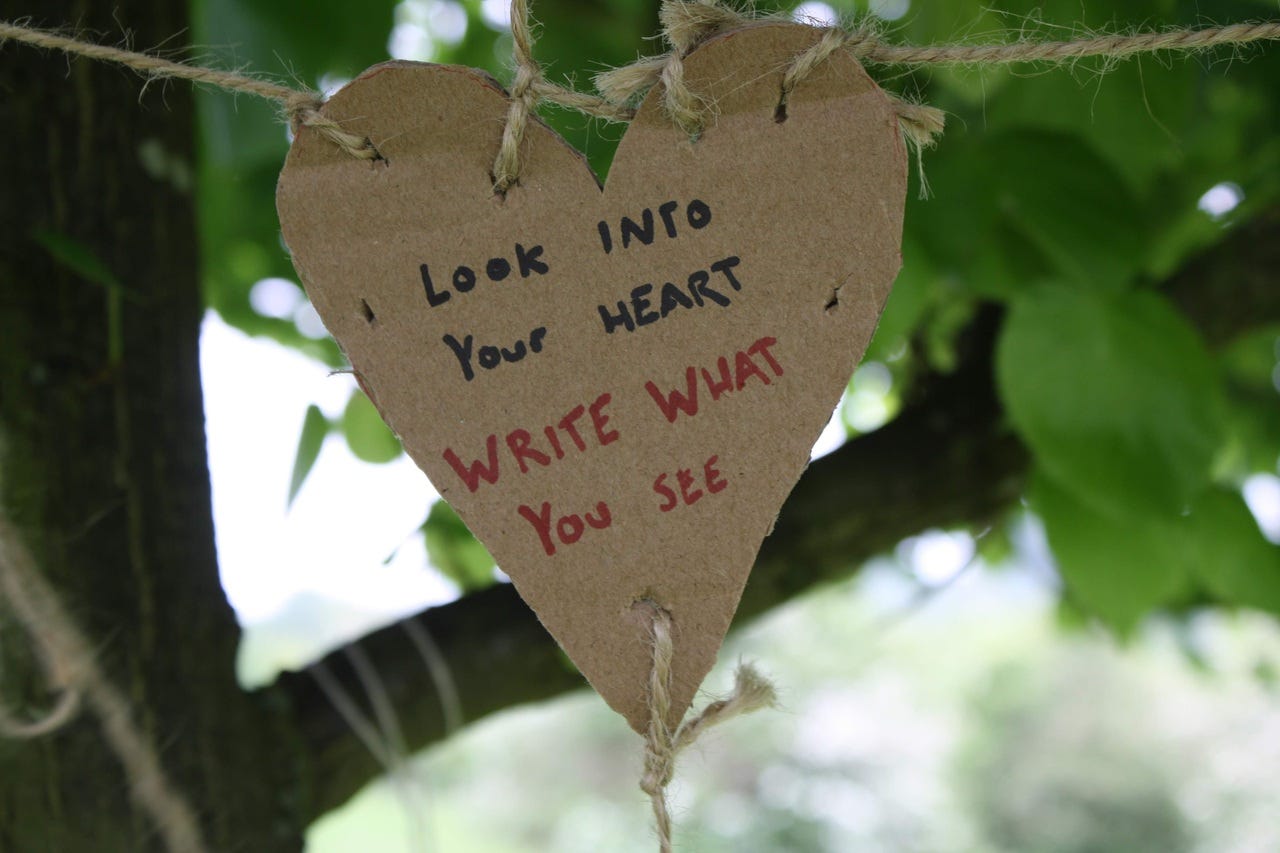

Despite my fascination with exploration, I’m cautious about reading other people’s accounts of walking. When it comes to telling the stories of my wandering, it has always seemed more important for me to dig deeply into my own experiences through exploring my journals and photographs.

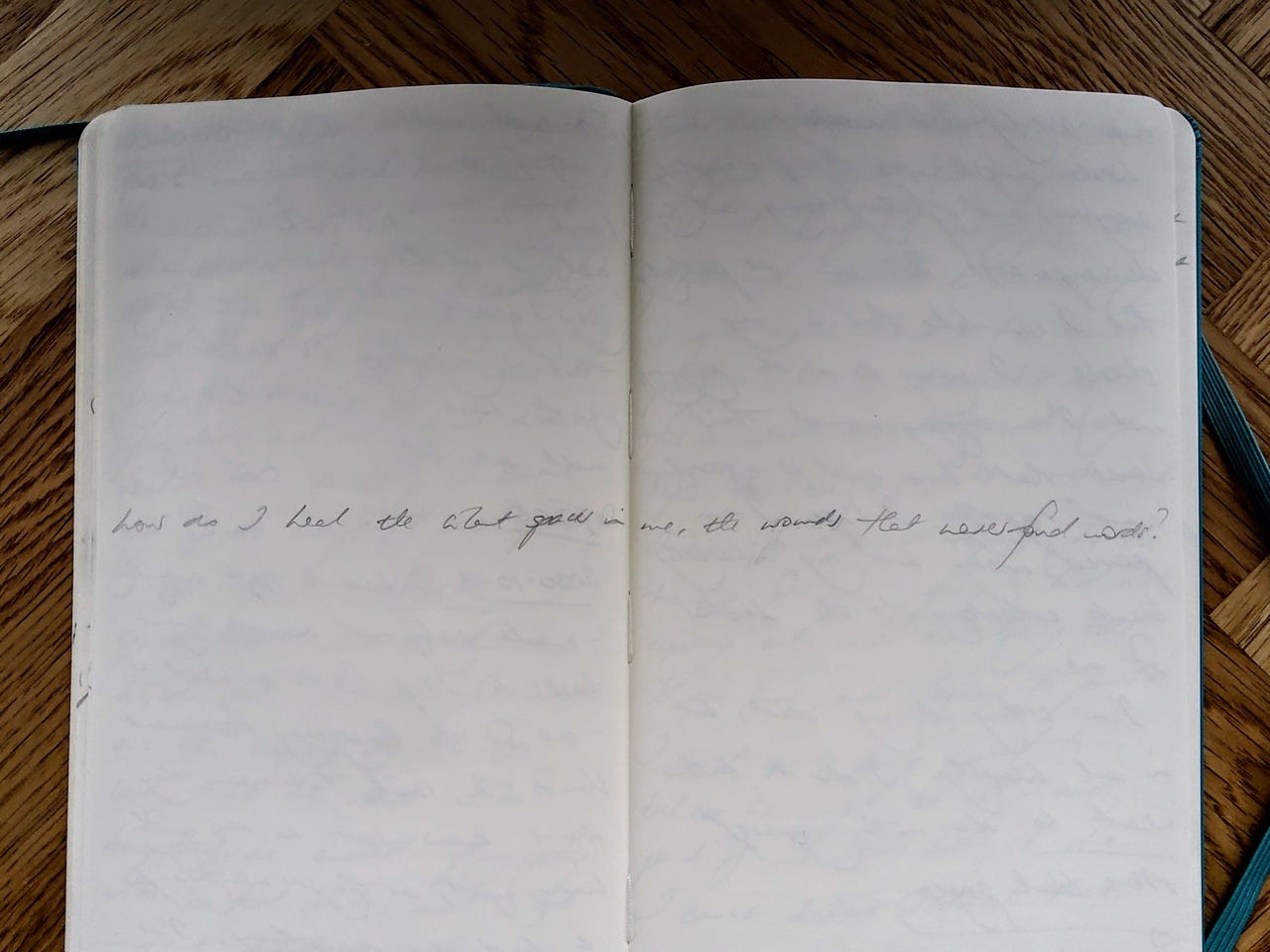

As someone who lives with severely deficient autobiographical memory (SDAM), I can’t mentally time travel to relive my experiences or set foot on old paths again. My mind simply doesn’t allow me the confidence that any moment exists besides the time I am living in today. But I need my stories to be my own.

I recall bare facts about the past, and I carry a deep sense of knowing in my bones. I relive my memories through the words and pictures I captured at the time, and weave stories from those sources. But in my reality, my memory is always constructed, never recalled. I stand aside from my own life as an observer, picking over scraps of evidence to make sense of what is true.

I am a story that I tell myself.

My personal history is incomplete, and the gaps and uncertainties often lead me to question the reality of my experiences. My faulty memory can feel like an insurmountable obstacle as I aspire to write creative nonfiction, but it is a challenge even when I recount a story to a friend. Is this story I am telling true, or have I simply told it enough times that it feels true?

There are times when my self-interrogation can be ruthlessly destabilising. This week, as controversy swirled in the media about truth-telling in writing, I’ve been trying hard not to lose myself in a maelstrom of doubt.

The constancy of values

In the midst of uncertainty, one constant is my values. I am someone who aspires to be honest, brave and kind.

Given the faults in my memory, I’ve always felt it’s easier to be honest. Since my memory cannot easily parse the difference between a simple truth and an oft-retold fiction, I cling to what I know to be real. Before I understood that I have SDAM, I often felt embarrassed and awkward about my not knowing, but I'm increasingly at ease being, at times, a stranger to myself. It’s hard to admit that I don’t remember events, people and places, especially if they are important to someone I love and care about. But it’s always better to admit to the holes in my memory than fill them with the chattering voices of uncertainty.

True honesty is characterised as total. “Unflinching”, Penguin put it in their marketing of The Salt Path, a phrase they may come to regret. But in my experience, honesty is progressive and malleable. There are things I earnestly believed about myself two decades ago that I now know are not entirely true. Honesty responds to learning, self-discovery and revelation, and truth accumulates as it attracts facts, experience and perspective. An honest mind can change, if it is open to grasping its past misunderstandings and errors.

Everyday honesty isn’t about dramatic revelations. For me, being honest starts with being comfortable looking at myself in the mirror. It’s about recognising that sometimes I have difficult feelings about myself. I am learning to be OK with not knowing myself as much as I am with knowing.

That’s where being brave comes into play. Our culture has given many of us an overblown view of bravery. I used to believe that bravery was about rushing into burning buildings, standing on cliff edges or jumping out of planes. By that measure, I am not brave. But for me, being brave means facing up to my anxieties and worries, and deciding that I am going to carry on regardless. Bravery comes as I make small steps towards the future that I want for myself. As I practice being brave, I grow in confidence. And as I grow in confidence, I find more opportunities to be brave.

And all of this is balanced with kindness, to myself and others. Untempered honesty, hot with bravery, is an unforgiving sword. Kindness enables a truth-telling that opens a path towards progress, rather than cutting people off at the knees. Kindness does not afford the indulgence of flattery or insincerity, but it does meet the truth-hearer where they are. The kindness I extend to myself recognises my complexity, and it encourages me to see the obstacles that others face, too.

There is something magical in the interplay between these values of honesty, bravery and kindness. I see they compensate for and balance each other. Two values can find themselves in binary opposition, forcing unnecessary choices. But these three values exist in a trinary relationship, reaching out to embrace and strengthen each other.

And all three of these values seem to circle love. I used to think love was only kindness, but I see now that love must find its expression in honesty and bravery too. Love is kindness, honesty, bravery woven together, the fabric of each shot through with the threads of the others.

Honest, brave, kind love is the foundation of my truth-telling.

Reassessing The Salt Path

In the wake of the Observer’s allegations, I’m sure that armchair investigators, hell bent on the pursuit of justice, are picking over tide tables, weather reports and route maps to interrogate the story of The Salt Path. Many people, especially those faced with long-term health conditions, have every right to be angry and confused. But I don’t want to add to the fury currently directed towards Sally and Tim Walker, as Raynor and Moth Winn are known in real life.

Reflecting on the events of the last week, I have come to the conclusion that I am not in any way surprised by what has unfolded. It's human nature to want to tell the truth of our experiences, but it's also human nature to want to protect ourselves from shame. Edits, reimaginings and omissions are inherent in the art of memoir; creative non-fiction is creative, after all.

But I wonder if The Salt Path may have come unstuck because of simple misrepresentation. It's impossible to say where the blame for this lies. But authors, publishers, movie makers and publicists should know that there's a line somewhere between “unflinchingly honest” and “based on a true story”, and that people deserve to be able to tell the difference.

Yet, in a sense, all the stories we tell are based on a true story. Even if we can vividly relive our memories, we will never see any perspective except our own. Human lives are too complex, interwoven and shifting ever to be fully grasped. Our brains do not have the capacity to hold on to every detail of everything that ever happened to us, let alone accommodate every alternative perspective. Our truth-telling will always be partial, emergent and cumulative.

There can be truth in fiction; there may be lies and omissions in nonfiction. Perhaps the most important lesson of The Salt Path is that the line between these genres may be even blurrier than we dare admit.

What matters most of all, I think, is what motivates any of us to tell stories about ourselves. Grounded in honesty, bravery and kindness, truth-telling can have a transformative power that runs far ahead of the distinction between what is real and what is not. Truth-telling becomes a moment of connection, as one human heart is revealed to another. That fact is worth holding on to.

Valuing your path

For now, I’m mentally recategorising The Salt Path somewhere at the very blurry edge of creative non-fiction. It may still be a valuable book, despite the controversy surrounding it. I can only hope the full story comes to light, and everyone involved can move beyond their initial defensive posturing so that readers can better understand the veracity of the book.

If you were inspired to walk by The Salt Path, I can understand how the messiness of the last week could be destablising. But it does not diminish the reality of your experience. Every step you have taken is yours. The journeys you make will still meet you in the simple truth of their existence, and invite you into the wonder of discovery. You have no need to doubt your own path.

And whether you write about your experiences or simply tell your stories to family and friends, lean into your values. Cling to them. Let them shape the path you walk. They may not lead you to a bestselling book and a movie deal, but giving an honest, brave and kind account of your life is a path of integrity and authenticity. And it's always worth following.

Thanks for writing this Dru, I loved the Salt Path when I read it shortly after it came out and I'm saddened that someone decided to spoil the story by saying it wasn't exactly true.

Lovely stuff Dru, thank you