There are so many things I love about the place I live. I am privileged to walk on wide sandy beaches, with mountainous skies and heart-stopping sunsets. But sometimes, I miss the gentle meandering of leafy trails.

In a land where the salty wind bends solitary trees towards the earth, woodlands are rare. But there is a lush, green stretch on a bend in the river Wyre, nestled in the lee of a small hill and edged by reed beds. Even on the most blustery days, the piercing wind is slowed by swaying branches and there is stillness close to the ground.

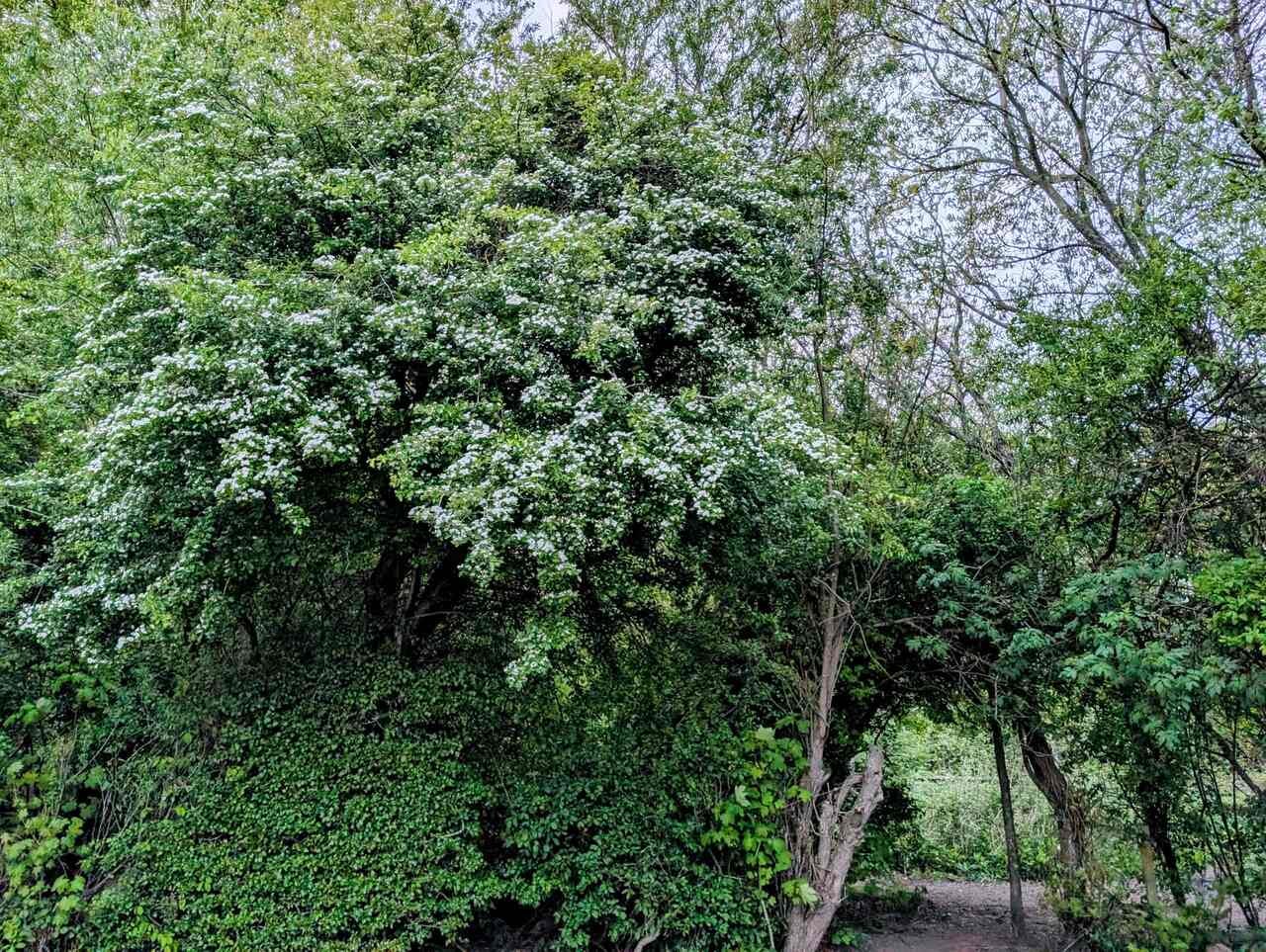

And on the path by the river bank, there is an abundance of hawthorns.

Meeting hawthorn

Hawthorn is native around the northern hemisphere from North America to the furthest reaches of Asia. Here in the UK, we have two species. The common hawthorn (crataegus monogyna) is widespread across the country, while its cousin the midland hawthorn (crataegus laevigata) grows mostly in the heavy clay soils of England's centre and south.

Young hawthorn has a smooth, grey-brown bark that cracks as it ages and spreads its characteristically dense, thorny branches. It can grow tall and wide, and the most ancient hawthorns can easily reach two hundred years old. In spring, hawthorn’s abundant green leaves emerge soft and lobed with serrated edges, each no bigger than the palm of a small child’s hand. Delicate stems carry clusters of tight buds which burst into creamy white blossom, giving way in autumn to an eye-catching display of bright red haws.

Adaptability is the key to hawthorn’s strength. It is a woodland plant, often among the first shrubs to establish itself, offering protection to slower growing trees that sprout beneath the thicket of its branches. But you'll also find it in hedgerows, on mountains and in marshes, sometimes gathered with its kin but equally growing alone. And it adapts to coexist with humans. It gladly makes its home in our urban environments, even tolerating poor soil in wastelands and air pollution from busy roads.

But what makes hawthorn remarkable is the abundance of sustenance it offers to other life. Its closely packed branches are a safe shelter for nesting birds. Its flowers provide rich nectar for bees and are a beloved food of dormice. Its leaves nurture the larvae of more than a hundred species of butterflies and moths. And come autumn, its berries will feed countless members of the more-than-human community through the dark half of the year.

Humans and hawthorn

Since ancient times, humans have recognised that there is something special about the hawthorn. Its flowering at the beginning of May coincides with the celebration of Beltane, the Celtic fire festival which falls halfway between the spring equinox and the height of midsummer.

For ancient agricultural societies, Beltane was a celebration of fertility and renewal. In Irish traditions, herds of cattle would be driven between twin bonfires to be purified and protected by smoke and ash. Couples would leap over Beltane fires in celebration of their union. It was a time for handfasting and for young lovers to go a-maying, wandering in the woods and returning with grass-stained knees and backsides.

As spring turned to summer, hawthorns were decorated, celebrated and revered. Hawthorn’s flowers and leaves were used in decorative garlands, and its fast burning wood fueled Beltane’s bonfires. Its stripped trunk was the origin of the maypole, and it became a potent symbol of fertility and sexual union as the ribbons of men and women were intertwined around its phallic form.

But as plagues swept through Europe, the hawthorn took on darker meanings. We now know that its flowers emit trimethylamine, one of the first chemicals formed in decaying flesh. But for people facing the unstoppable force of death, the scent of hawthorn made it a tree to be feared.

For modern pagans, hawthorn remains a tree of enormous symbolic significance. But its associations with fertility can be troubling. Beltane celebrations that historically centred on the abundance of nature projected human ideas about the union of masculine and feminine onto the hawthorn. And today, the unthinking conflation of sex and procreation often excludes those of us who are queer, trans or non-binary.

Biological diversity

“Biological” is a word that has dominated headlines over the past few weeks, as a ruling from the UK Supreme Court threatened to exclude trans people from many aspects of public life. Like so many others, I've been protesting this injustice. And I'll continue to stand in unwavering solidarity with the trans women and men whose lives are profoundly affected by the court's misconceived understanding of what it is to be human.

Human biology is complex. Sex is not simply a matter of chromosomes, but of hormones and bodily characteristics. Each of those aspects is a spectrum, not a binary. Even before we get to the myriad ways we self identify, present ourselves and are understood by others in the diversity of our genders, we humans cannot be easily divided into two simple camps of “male” and “female”.

Culture is slow to change in grappling with the inherent complexity of human life, and reactionary forces seek to confine us in the name of what they believe is “natural”. Too many people are harassed, hurt and killed because they do not conform to other people's simplistic notions of “biological” sex.

But if we only looked beyond humanity’s narrow definitions to the incredible diversity of the more-than-human community, we might begin to tell a different story. Hawthorn can shows us the way.

Generative wholeness

Like humans, each hawthorn carries the genetic inheritance of its parents in its DNA. Unlike us, every hawthorn flower carries both reproductive cells that are required for creating a new life.

But a solitary hawthorn cannot conceive its child alone. A friendly bee carries the pollen of one tree to another, and the potential of a new life emerges in a hawthorn berry. In human terms, every one of a hawthorn’s flowers could become the mother or father of a new being. And each blossom contains the possibility that it will be either, neither or both.

And even if an individual flower never becomes a berry, the hawthorn tree offers the gift of its nurturing and generative strength to the community that surrounds it. The oak sapling growing beneath its boughs is fostered to maturity by the hawthorn’s protection. Generations of fledglings call hawthorn their home. Hawthorn leaves sustain countless caterpillars on their journey to the transformative chrysalis, and butterflies take flights of freedom from its branches.

There is so much more to the generative possibilities of life than the union of masculine and feminine. Hawthorn teaches us that we can meet the world in our wholeness, carrying within us the potential to birth a new world around us. We are never simply an incomplete half waiting to meet its match. We are already everything we need to be. And from our wholeness, we can make allies with those who see us as we are, and become a creative force in the emergence of generations of living beings.

Being with hawthorn

In times of conflict, sadness and distress, being in nature can offer us solace and comfort. Time apart from other people affords us the chance to be who we are beyond the judgemental gaze of those who do not recognise our humanity.

But being with the more-than-human also offers us the gift of learning and growth. Hawthorn has so much to teach us about what it means to be human. Here are some ways to approach this magical being:

Find a hawthorn tree and observe it closely to appreciate the diversity of life it supports. Engage all of your senses. Notice the different insects visiting its flowers, caterpillars crawling on its leaves, the birds nesting in its branches, and the variety of plants growing in its protective shade.

Meditate on hawthorn's adaptability and resilience. Hawthorn is alive with its own intelligence and desires. Spending time with a specific hawthorn, you might notice how it has shaped itself in conversation with the wind, responded to soil conditions, and bloomed with the growing strength of the sun.

Use journaling to explore your own generative abundance, inspired by the hawthorn's biology. Consider the idea that, like the hawthorn blossom carrying all the potential of life within it, you too hold a wealth of creative possibility. How can the human and more-than-human community benefit from the gift of your wholeness?

Make an offering of thanks to a hawthorn. The simplest and best gifts sustain life, and pouring drinking water is a potent symbol that another being's survival is of equal importance to your own. If you feel compelled to leave a physical gift, find a beautiful stone to leave beneath the tree or loosely wind a biodegradable thread around a branch.

The diverse community of the living world welcomes and accepts you exactly as you are. Offer a hawthorn the same gift of loving attention, and see what it can teach you about being human.

Beautifully written...

And it also helped a lot with my Ogham studies!!

We are lucky enough to have a few acres of land surrounded by the wonderful hawthorn, we've let one of the hedges grow out, the others are battered biannually by our neighbours flail trimmers, both thrive. One thing we discovered when trimming a hawthorn (to allow a little light into our orchard) is that the trimmings can root and all of a sudden you find you have become a foster parent to multiple new hawthorn plants! I treat it as one of the three special trees, Oak Ash and Hawthorn.