Last week was my birthday. After a busy and stressful 2024, my partner Karl initially suggested a remote countryside retreat. But feeling the need for convenience, connection and culture, we headed instead to Manchester for two nights of immersion in the sights and sounds of the city.

For once, a change was as good as a rest. It was a wonderful weekend. We wandered the icy streets, revisiting the places that had shaped Karl’s journey to adulthood. We popped into pubs, dawdled by canals and gazed at buildings. We feasted, partied and shopped.

And we had two remarkable experiences that challenged my preconceptions about what nature is and where we might find it.

Understanding nature

Nature is a tricky concept. “Contested” was the adjective my university geography lecturer most often used to describe it. I remember that their critical geographies of nature module was mind-expanding, offering a deep dive into thinking about the complexity of ideas about the nature world and how we have understood it through the ages. It stays with me.

In modern thinking, there is a deep divide between nature and culture. Humanity's artefacts - cities, roads, cars, coal mines, factories, pollution, books, music, and art - seem to stand apart from the natural world. The Cartesian dualism of human culture and wild nature has shaped our civilisation for hundreds of years.

Setting humans against nature leads to all sorts of problematic answers: fortress conservation that pushes indigenous populations out of connection with the land; urban environments that are scrupulously cleared of every unwanted plant, bird and rodent; and polluting journeys to remote places that are playgrounds for the privileged.

Yet there's nothing we have made that doesn't find its roots in the earth's resources. Humanity cannot create something out of nothing, not even itself.

Enclosed in our homes, with comfy sofas, artificial lights and air conditioning, wildness can feel remote. But every part of our bodies is made from the stuff of the universe. Our cells are fueled by the food we eat. We breathe the same air that gives life to animals and plants. The water we drink once fell from clouds, shaped mountains, and flowed through rivers into the oceans in a neverending cycle.

Yet, our binary distinction between nature and culture persists. When we talk about walking in nature, we imagine there is a realm of human activity we can leave behind to enter a world that is other than we are. So, we seek green and blue spaces that teem with more-than-human life to find restoration in the reconnection.

But we have never been disconnected from the web of life. We are nature, just as much as the eagle, the whale and the beetle. We walk in nature on city streets because we are nature wherever we go.

Seeing nature

Our visit to Manchester was driven in part by the opportunity to see a remarkable, immersive exhibition of David Hockney's work.

Bigger & Closer (Not Smaller & Further Away) is a retrospective of Hockney's prolific career. Famed for his paintings of Californian swimming pools in the 1960s, his work has evolved through stage design, photography, collage and latterly, landscape paintings of his native Yorkshire made with his iPad.

Sitting on the floor of the exhibition hall, it struck me that Hockney is an artist who has dwelled perpetually at the blurred boundary between nature and culture. The show charted his fascination with water, the curving shapes of Los Angeles' canyons, and the colours of northern Britain’s trees, fields and hills. It was a beautiful and moving experience to be surrounded by projections of his work on four walls and the floor, listening to him talk about his artistic process, soaking in more light than my brain could process. His enthusiastic adoption of digital art made it possible to be wrapped inside his creativity as his unique view of nature took shape around us in bold, dynamic strokes.

"The world is very, very beautiful if you look at it," he said in his voiceover, "but most people don't look."

Beauty, like nature, is an elusive concept. But shrouded in January fog, the city streets outside the exhibition had an ethereal beauty all their own. Buildings projected themselves into blurry darkness, and soft pools of light illuminated the pavement beneath street lamps. Wrapped up against the cold and walking slowly, I found so much beauty in the city. Vibrant graffiti, monumental architecture, glowing shop windows. Slender birches, persistent buddleia, lichens, algae and moss. Swirling mist, low clouds and slow-moving canals. It was all here for the seeing.

Wild nature

The other reason for us to visit the city was an exhibition at Manchester Museum called Wild.

Like nature, wildness is an idea shaped by the modern constitution that pits humanity against the environment. The concept can demand critical thinking, but the Wild exhibition began gently with depictions of nature in art, from Romantic seascapes to William Morris’ plant-inspired wallpaper. Visitors were invited to draw and write in response about what the wild meant to them.

Perhaps ironically, contrasting with Hockney’s approach to nature as an observer, Wild championed the potential for human intervention. “Wild is about how people are creating, rebuilding and repairing connections with nature,” read the exhibition’s introductory panel.

The exhibition was a series of snapshots, offering insights into the conception of wildness in locations as varied as the seabed around the Isle of Arran and the diverse landscapes of Yellowstone National Park. It was heartening to see such a reflective approach to America’s open spaces, which highlighted how both indigenous populations and apex predators were forcibly displaced to create the illusion of an idealised, pristine wilderness.

National parks are as much a human invention as urban landscapes. Closer to home, I found the exhibition’s discussion of Manchester’s biodiversity particularly fascinating. “Cities are not just full of people,” stated an interpretation panel. “They are also home to a diverse range of species: some we notice and like, others we notice and don't like, and others we simply ignore.”

I left the exhibition thinking about dandelions and rats, the uncontrollable wildness of nature that pushes through pavement cracks and scurries through drain pipes. My desire to make space for the more-than-human in cities has its limits, and maybe that's OK. But I can always do more to celebrate and appreciate the abundant diversity of urban life, even those elements of it that I find unsettling. The city is a home I share with others.

Rethinking nature

It's undoubtedly true that access to wild nature is good for urban dwellers, yet too many cities lack breathing space. Less than half of Manchester's population lives within 200 metres of even a small green space, and the city centre's crowded towers of glass and steel isolate more and more people from the earth beneath their feet.

Reaching a park can mean crossing a busy road. Concrete abounds. In areas of redevelopment, trees are purposely introduced in ornamental planters, even as nature’s unmanageable encroachment is pushed back. Tumbling weeds in derelict sites, havens for bugs and butterflies, are slowly being cleared to usher in a more manicured future.

There are seeds of hope, though. In a post-industrial city devoid of unmodified natural habitats, Manchester's planners envisage expanded wildlife havens, connective corridors and more welcoming living spaces for the more-than-human in parks, cemeteries and allotments. The city can become a place where humans and other species coexist in tangled, complicated, shared spaces.

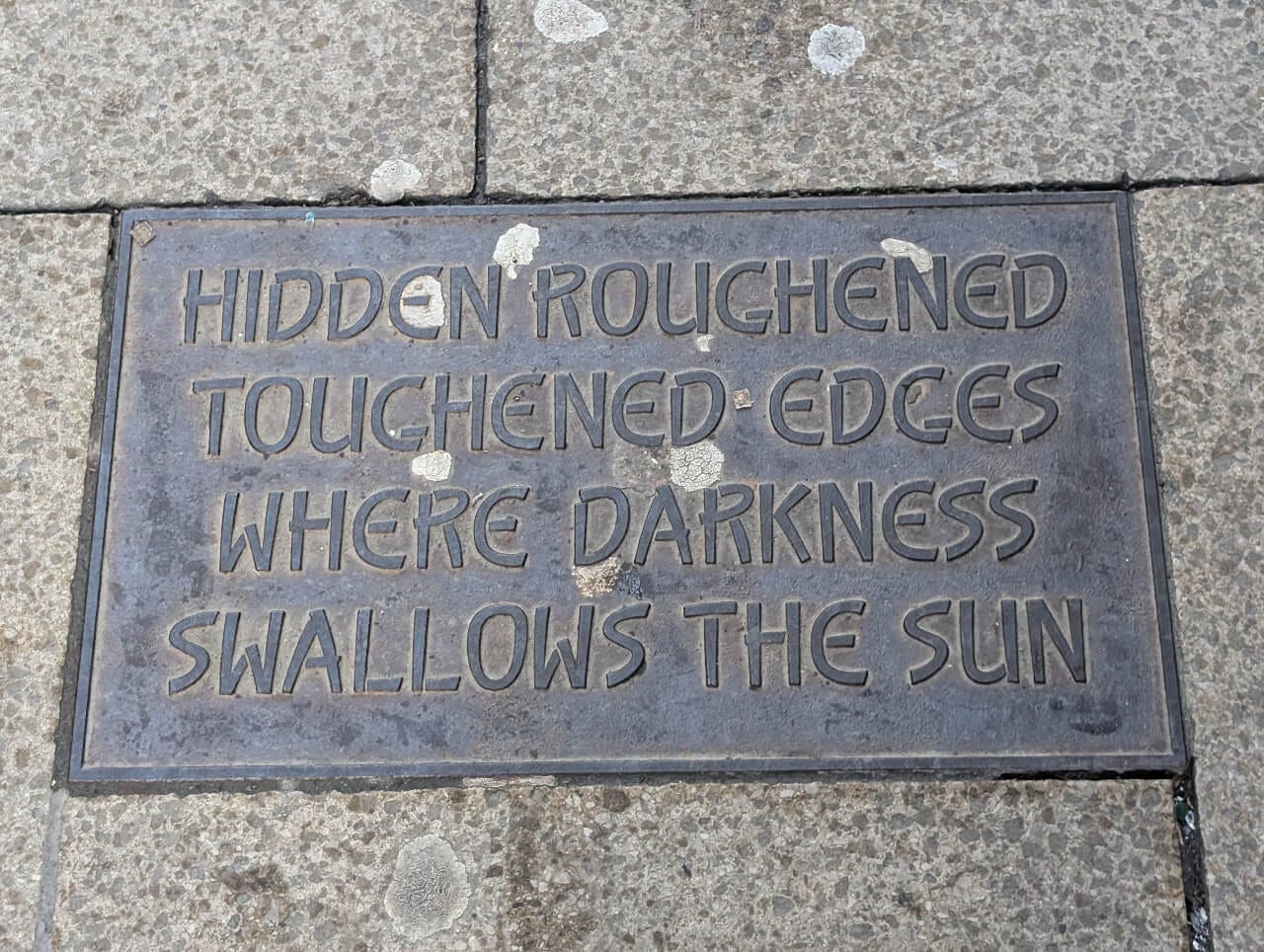

Perhaps that's the future for all of us. It certainly makes the wild city exciting and intriguing to explore on foot. I believe the best walks can start on our doorsteps, even when we're deep in the urban jungle. There’s always something inspiring to discover, whether it's poetry embedded in a pavement or a tenacious wildflower clinging to a crumbling wall.

Maybe opening our eyes to the diversity and beauty of nature and culture around us, wherever we are, is the key to respectfully taking our place in the family of all beings as the wild human creatures that we are.

Discover more

Pete Kalu wrote a thought-provoking review of the Hockney exhibition a few weeks back, which I highly recommend reading. If you want to see the exhibition for yourself, you can get one of the last few tickets here. It runs until 25 January.

And Wild, at Manchester Museum, is open until 1 June. It currently features a pop-up exhibition about the work of Black Girls Hike, who champion the engagement of Black women in nature connection and outdoor pursuits. Admission is free, but you can reserve a ticket and make a donation in advance.

A great read. 'Shrouded in January fog' - feels like Hockney is still influencing how you see the world - always a good sign. The Nature-Civilization split thoughts are food for thought - the rats and dandelions!